Learning Outline

Integumentary System

Integumentary system

Integument

- Integument = skin

- Only one organ in this system—but it’s the largest organ of the body

- Therefore, the skin is an organ AND a system

- A few biologists designate nails, hairs, and/or the fatty layer under the skin as separate organs that are part of the integument—but here, we take the more common approach to designate the skin proper as the single organ of this system

Functions of skin

Protection — mechanical, UV radiation, immune “first line” and “second line,” water conservation

Excretion — sweat glands excrete “waste”

Chemical synthesis — vitamin D

Thermoregulation — can regulate heat loss or conservation

Sensation — various sense of touch, temperature, vibration, pain

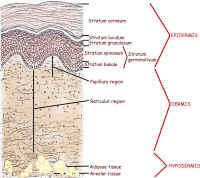

General structure

Epidermis — stratified squamous epithelial outer layer

Dermis — dense fibrous connective inner layer (usually thicker than the epidermis)

Hypodermis — loose fibrous tissue under skin (hypodermis is NOT part of skin, but where else can we discuss it?)

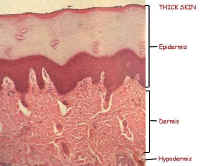

Thickness varies

Thick skin — Thickest skin found on palms, fingertips, sole

Thin skin — Thinnest skin found on scalp, near lips

Thick skin (stained microscopic section)

click the image to enlarge it

Thin skin (stained microscopic section)

click the image to enlarge it

Epidermis

Structure

Composed of different strata, the outermost of which are comprised of dead cells

- Cells divide only in base layer, then die as they are pushed outward

- Form a “keratinized” layer on surface that protects

Epidermal growth factor (EGF)—regulates growth of epidermal cells and helps to stimulate healing when the epidermis is injured

Strata

Listed here from deep to superficial) ![]()

![]()

- Stratum germinativum (“growth layer”) — made up of two sublayers

- Stratum basale (“base layer”)

- Several types of cells, two of which are important in our discussion

- Keratinocytes

- Keratin (tough, water-resistant protein)

- Melanocytes

- Melanin (brown protein pigment) is produced by melanocyte cells in base layer

- Melanin, being dark, absorbs UV radiation

- Melanin is released by melanocytes, which have long extensions, and absorbed into surrounding keratinocytes

- Melanin production is regulated in part by a family of hormones called melanocortins

- Produced by keratinocytes in response to UV radiation (tiny amounts from anterior pituitary)

- Melanin production is regulated in part by a family of hormones called melanocortins

- Two categories of melanin

- Eumelanins — dark brown

- Pheomelanins — light brown/red/orange

- Melanin (brown protein pigment) is produced by melanocyte cells in base layer

- Cells of stratum basale are closest to the blood supply in the dermis and are thus the healthiest

- Only these cells can reproduce

- Stratum spinosum (“spiny layer”)

- Cells are pushed from below and become “squished” and look “spiny” on cross sectional view

- Spiny appearance also comes from spot desmosome connections to nearby cells, which can pull out “spines” as the cells shrink away from each other when prepared for microscopy

- Because the cells are farther away from the dermal blood supply, they are less healthy and thus don’t reproduce

- Cells get sicker and sicker as they are pushed away from the dermis

- Cells are pushed from below and become “squished” and look “spiny” on cross sectional view

- Stratum basale (“base layer”)

- Stratum granulosum (“grainy layer”)

- As cells from stratum germinativum die, they enter stratum granulosum

- All cells here are dead (and look grainy when stained/ no nuclei)—but biochemical changes are happening inside them

- Keratohyalin (a precursor to keratin) forms in granules here

- May be missing in some thin skin

- Stratum lucidum (“light layer” or “clear layer”)

- Keratohyalin is transformed into eleidin, which is almost transparent, making this layer look almost “clear”

- May be missing in some thin skin

- Stratum corneum (“horny layer” meaning “like an animal’s horn” —not what YOU were thinking!)

- Keratin is fully formed

- Flattened cells filled with keratin form “keratinized layer” and make this “keratinized stratified squamous epithelium”

- These dead cells are sometimes called corneocytes

Dermis

Epidermis joins dermis at the glue-like dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)

- Also called dermal-epidermal junction

- Is an example of a basement membrane (BM)

Dermis is irregular dense fibrous connective tissue

Two layers of the dermis:

- Papillary region

- Outer (superficial) region of dermis has bumps called dermal papillae

- FYI — bumps in the human body are OFTEN called papillae (sing. papilla = “nipple”)

- Increase surface area for glue to “hold” more tightly

- In thick skin, arranged in rows to form epidermal ridges (friction ridges)

- “Prints” of hands/fingers and feet/toes to improve grip (and to identify the perpetrators of crimes against professors)

- Amplify sensation of textures

- Outer (superficial) region of dermis has bumps called dermal papillae

- Reticular region

- Deeper area of the dermis has irregular swirls of collagen fibers plus nerves and nerve endings, blood vessels, sweat glands, and more

- Reticular = “netlike”

Scars

Hypodermis

Also called “subcutaneous tissue” (sub = “under” cutaneous = “skin”)

Also called “superficial fascia”

- Fascia ( = “gang”) is made up of loose bundles (“gangs”) of fibers

- Superficial fascia is under the skin; deep fascia is among the muscles

Loose fibrous tissue

- areolar (loose, ordinary) connective tissue

- adipose

- formed when fat cells of areolar tissue grow large and dominate the tissue

Includes

- skin ligaments—denser bands of fibrous tissue that help anchor the skin to underlying structures

- Nerve fibers and sensory receptors

- Blood and lymphatic vessels

- Immune cells

NOT part of skin proper

Functions

Protection

Thermoregulation

Shape

Storage of fat (fuel storage)

Recommended link: Skin Histology This is a brief set of microscopic images to help you understand the structure of the skin

Hint: You will be tested on the correct anatomical order of any/all layers of the skin and associated structures (deep —> superficial AND superficial —> deep)

General structure of the skin (microscopic cross section)

Click the image to enlarge it

Required Mini Lesson: Fascial System

Derivatives of skin

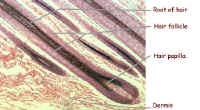

Hair

Grows from hair follicles (follicle = “little pocket”)

- There are approximately 5 million hair follicles on your body, of which about 150.00 are on your head

- Hair papilla is bump at base of pocket

- Covered with stratum germinativum

- Place from which the hair grows

- Location of stem cell that provide cell replacements for rest of skin

- Arrector pili

- Small muscles attached to follicle and dermoepidermal junction

- Contract when a person is chilled or stressed

- Additional arrector muscles in the skin around the nipple cause the nipple to become erect

- A&P trivia: do you know what the word horripilation means? (click it to find out!)

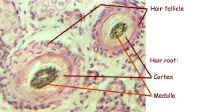

Hair shaft (visible part) and root (not seen; in follicle) ![]()

- Dense, cylindrical modification of keratinized layer

- Inner part: medulla

- Outer part: cortex

- Shape can affect curling (flatter = curlier)

Usually pigmented with melanin

- except in white hair (such as in the platinum blonde highlights sported by your professor)

- cortex can be pigmented differently than medulla

Hair follicle (microscopic longitudinal section)

click the image to enlarge it

Hair follicle (microscopic cross section)

click the image to enlarge it

Nails

Platelike, denser version of hair (never pigmented in humans)

Nail body is visible part; nail root is still in follicle (nail groove)

- Usually no pigmentation (easy to see changes in blood color under nail)

- May have pigmented streaks

- Lunula (= “little moon”)

- Whitish crescent at base of nail

- Base of nail root is fused with connective tissue covering bone of finger—thus stabilizing the nail

Nail bed is skin under the nail

- Stratum germinativum only

Human nail

click the image to enlarge it

Sweat glands

Sweat glands (also called sudoriferous glands) are exocrine (ducted) glands ![]()

Sweat contains mostly water plus some excretions and secretions (such as pheromones [sex attractants])

Different types of sweat glands ![]()

- Eccrine — primarily thermoregulatory

- Apocrine — involved in stress response

Sebaceous glands

Sebaceous glands are exocrine glands

Secrete sebum or “skin oil”

- sebum conditions hair and skin to prevent damage

Surface film

Combination of sweat, sebum, dead cells, bacteria, etc.

Microbiome: interacting populations of microorganisms living on the skin

Skin color

Genetic factors

Examples: inheritance of basic skin color, freckles, albinism

Environmental factors

Example: ultraviolet [UV] radiation, dyes [tattoos]) ![]()

Physiological factors

Examples:

- ß-carotenes from food

- Hormones such as ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) and other molecules related to melanocortins

- Blood volume/color

- Oxyhemoglobin is bright red; carbaminohemoglobin is dark red

- Cyanosis is bluish color of skin from dark red blood

- Jaundice (bile pigments build up in skin)

Human skin color varies widely, mostly from the presence of different types and amounts of melanin in the epidermis, as seen in these three photos of young girls.

Left are Maasai girls from Tanzania, Africa.

Middle are villagers from the upper Amazon, Peru.

Right is my daughter Aileen (Euro-american) in 1994.

Click the image to enlarge it

A strange case of the blues . . .

Stan Jones, the Libertarian candidate in Montana for the U.S. Senate in 2002, turned blue from taking home-made colloidal silver solution. He took the solution as a preventive antibacterial agent. It caused argyria, which caused silver crystals to form in his skin which, along with stimulated melanin production, made Mr. Jones’s skin look gray-blue.

Interested in skin? Check out Skin: A Natural History

Thermoregulatory functions of the skin

Blood in the dermis is like the fluid in a radiator, bringing heat from other parts of the body ![]()

Blood flow in the dermis increases or decreases as the body tries to gain or lose heat

Conduction

Heat is conducted from blood through skin to air (or water or the chair you are sitting on right now)

Convection

Warm air rises (because it is less dense than cool air), creating a convection current that draws cooler air in behind it

Radiation

Heat travels as radiant energy (like light or radio waves), specifically as infrared (light waves beyond visible red)

Evaporation

When water turns to steam (evaporation) heat moves (from skin) to the water molecules as they leave as water vapor

Click each photo to enlarge it

The African elephant (above) provides an extreme example of the skin’s thermoregulatory function. The front of the animal’s ear (left photo) shows the ear’s great size relative to its head and body—but very thick skin. Notice the lighter areas—these are highly keratinized patches. The back of the ear reveals very large vessels near the surface of the very thin skin (no light patches). The elephant can regulate heat loss through its ears by exposing or not exposing the back of the ear.

Remember! Human body temperature varies!

Carl Wunderlich studied body temperatures of thousands of people way back in 1868 and pronounced the average human body temperature (oral) to be 98.6 °F (37.0 °C). ![]()

However, in 1992, P.A. Mackowiak’s research team used modern equipment and techniques and found that the human body temperature (oral) averages about 98.2 °F (36.8 °C). Here are their overall results:

|

Oral body temp

|

°F

|

°C

|

| Average temp |

98.2

|

36.8

|

| Upper limit of normal temp |

99.9

|

37.7

|

| Daily variability of temp |

0.9

|

0.5

|

What does this tell us? That body temperature, and other physiological variables, are not the same for everyone and even vary within an individual. This variability is NORMAL.

NOTE: Even though Wunderlich’s average body temperature has been revised to a slightly different number by Mackowiak’s more recent work, we usually still use the older numbers for the sake of discussion—a “ball park” number—neither average applies to any particular individual.

Readings, References, & Resources

A&P Core

Betts, J. G., DeSaix, P., Johnson, J. E., Korol, O., Kruse, D. H., Poe, B., Wise, J. A., Womble, M., & Young, K. A. (2013). Anatomy and physiology.

Khan Academy. (n.d.). https://www.khanacademy.org/science/health-and-medicine

Patton, K. T. (2013). Survival Guide for Anatomy & Physiology. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Patton, K. T., Bell, F. B., Thompson, T., & Williamson, P. L. (2022). Anatomy & Physiology with Brief Atlas of the Human Body and Quick Guide to the Language of Science and Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Patton, K. T., Bell, F. B., Thompson, T., & Williamson, P. L. (2023). The Human Body in Health & Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Patton, K. T., Bell, F. B., Thompson, T., & Williamson, P. L. (2024). Structure & Function of the Body. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Topic Focused

Coming soon!

Last updated: February 16, 2025 at 17:09 pm